Critical Technical Practice: “Just Do it”

Disobedient Electronics, edited by Garnet Hertz, was this week’s reading that introduced us to the topic of computational art as a critical technical practice.

It introduced us to a lot of different technoscientific art projects that have been designed to make a specific, often political intervention into discourse and events. These art projects are often practical and designed to aid activists in various ways.

Julian Oliver is a standout artist working in this space. His “Transparency Grenade” is a fantastic example of a disruptive object that subverts existing technologies to facilitate “transparency” in a possibly hostile or at least restricted environment.

It functions by using self contained network and computer hardware to wirelessly scrape local network traffic and send it to a new location where the data may be analysed and deciphered.

To me the form of the work is what elevates it into the art sphere – the obvious power and symbolic weight of the grenade lend a vivid and violent metaphor to the quietly invasive act of wirelessly hacking a network.

Presented in glass and stainless steel the exterior of the object draws heavily from the moneyed techofetishism of weapons fairs and marketing material, jewellery and high art. It imbues the work with a sense of well-crafted terror. This presentational “slickness” gives the raw activist message a “corporate” sheen, and ensures that it will be seen on pedestals in white cube gallery spaces. Similar to the Forensic Architecture work I’ve reviewed elsewhere on the blog – I think that taking subversive or activist messages into white cube spaces through intelligent use of aesthetics can be highly effective.

With that in mind, I’ll move on to my small attempt to put these ideas into practice.

Critical Technical Practice workshop

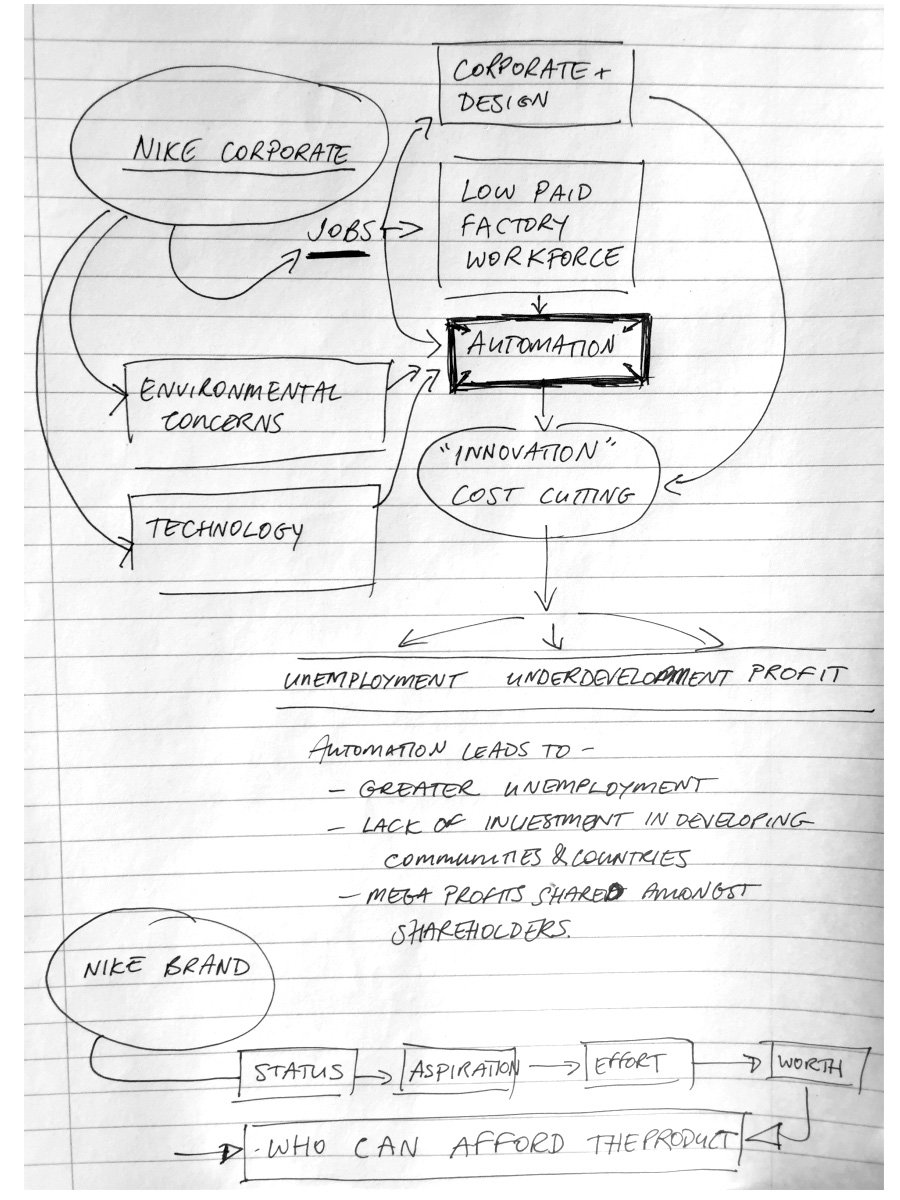

For our topic Ed and I discussed the Nike corporation and worked through the critical relations and entanglements it offers, of which there are perhaps too many to count.

I have chosen to focus on Nike’s workforce and its growing commitment to automation. Currently, Nike employs almost 1 million workers in factories around the world. There has been intense scrutiny into worker conditions, allegations of child labour, and low pay which have been extensively discussed in the past. There are arguments that Nike’s presence in developing countries has given communities access to a level of employment and pay that have benefited those areas. However, Nike are still aiming to drive up profits and drive down labour costs, and thus have been investing heavily in new automated technologies.

Another aspect of this automation revolution is that the cost-savings haven’t been passed onto consumers. Instead, shareholders and executives benefit, whereas workers who previously had opportunities are no longer required.

So, following this wave of automation into a speculative absurdist dystopia – when nobody has a job anymore, who can afford the products? It’s clear. The robots can. For my critical practice I’ve designed a ridiculous sweat band for an industrial fabrication robot. The sweat band provides hydraulic support and is grease-absorbent. Fetching colourways offer the technosingularity many viable ways of expressing itself. Best thing about it is that when the sweat band immolates after absorbing too much grease and coolant fluid, the robot can quickly whip up another one.